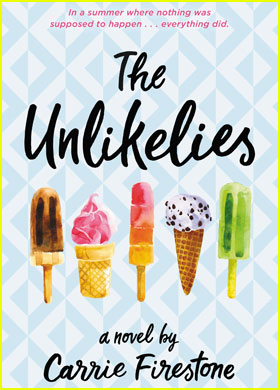

Carrie Firestone's 'The Unlikelies' - Read An Exclusive Excerpt From This Summer Must-Read!

The JJJ Book Club has an exclusive excerpt from Carrie Firestone‘s new novel The Unlikelies that you have to check out!

Set in the Hamptons during summer break – AKA the perfect summer read – The Unlikelies follows five teens as they form an unlikely clique and embark on a summer of vigilante good samaritanism.

Think The Breakfast Club meets The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks.

The Unlikelies hits shelves on June 6.

Check out the excerpt here:

WHEN THEY FINALLY released me, I slumped in the wheelchair while an aide paraded me through the brightly lit hallways and into an elevator, where a couple tried not to stare. Mom carried my plastic breathing thing and my blood-spattered shoes. Dad ran ahead to get the car, which my grandmothers had already filled with the get-well flowers.

The wait in front of the hospital, in the heat and bright sunshine, made me nauseated. I started to dry heave, and the guy pushing the wheelchair handed me a pink barf bucket. I had never felt so awful.

Click inside to read the rest of the exclusive excerpt from the novel…

That was when a woman came out of nowhere and took my picture. “Do you need me to come home? Because you know I will,” Shay said. She called or texted me hourly. “I feel so bad I’m not there.”

“I’m okay. Just sore. It’s not like you could do anything if you came home. I’m sitting around with ice on my ribs, trying to take deep breaths and listening to my mother tell the story to the relatives over and over again. If you want to help, send me really good noise-canceling earbuds.”

“Do you like the cranes?”

“I love the cranes.”

The origami cranes had taken over the house. People were dropping cranes on our porch with notes, with chocolates, with magazines, with flowers. Shay was the ringleader, the crane queen. It didn’t matter that I was pretty sure I was supposed to make the cranes myself for the healing to happen, or that I wasn’t on the brink of dying, or that it was all so melodramatic. Shay wanted to deliver a grand gesture, and I loved her for it. But I was uncomfortable with all the attention. I didn’t want people worrying about me.

The local newspaper published the horrible picture of me with my bandaged head holding a barf bucket on the front page with the headline GOOD SAMARITAN TEEN SAVES BABY FROM FUGITIVE FATHER. I sat on the living room couch, propped up on pillows, reading about the Alabama man who had fled his estranged ex?wife’s house with their baby girl to get back at the mom for leaving him. He had a history of domestic violence and drunk driving. There was a nearly full bottle of Southern Comfort in the passenger seat. I assumed that was the bottle he had used to beat me in the spleen. There was a shotgun in the trunk next to a stuffed owl wrapped in a pink box.

I watched the whole thing, which had been recorded on a tourist kid’s iPod. It was all a blur of sounds, mostly�head-cracking sounds and baby cries and sirens. Watching it over and over again was strangely comforting. I didn’t have to work so hard to remember.

It turned out there were many things I hadn’t noticed the day of the incident. I hadn’t noticed Daniela calling the cops or Sissy and old Mr. Upton banging on the back window of the car with a rock, trying to get to the baby. I only noticed those things the fifth time I viewed the video on YouTube. The first four times I was focused on the bizarre kicking motion my legs made while he drove the base of the bottle into my back. And then there was my ass crack hanging out when the cops pulled me from the car by my shorts.

I clicked on the TV news story that aired the night of the incident. The newspeople speculated the guy might have been planning to drive his baby off a cliff. They speculated he might have been gearing up to go on a shooting spree. People online said I was a hero. They said I was stupid. They talked about me, Sadie Sullivan, the girl named after her paternal great-grandmother, an Irish seamstress who saved seven children from a fire and burned the bottoms of her feet so badly they had to be amputated.

“Where the hell did they find out about that?” Dad said, leaning in to watch the video.

“I’m surprised the news didn’t say something about your thumb,” I said, referring to Dad’s missing thumb, a casualty of an accident he refused to discuss that happened when he was a New York City cop.

I wanted to stop watching, especially when they zoomed in on the blurred ass crack. I wanted to stop looking at the pictures online, especially the one of me in the wheelchair looking like a deformed larva. But I couldn’t stop. For two days straight, I watched and read and searched for more stories.

There was one story out of Alabama. A dark-haired newsman with a deep chin dimple told the story of the seventeen-month-old baby who was saved by the New York farm stand worker. They cut to a blurry photograph of the baby, with wisps of sandy hair and apple cheeks and a wide, drooling smile. “Thanks to that Good Samaritan, baby Ella is home safe with her mother and doing well.”

Her name was Ella. And according to my laptop, baby Ella was home safe and doing well.

I spent a week on the couch, sleeping, texting, reading online comments about baby Ella and me, fielding visits from family, from the remaining seniors (even Shawn Flynn and D?Bag stopped by with flowers), from my food-pushing grandmothers, who didn’t understand I was drinking all my meals through a straw.

Seth sent a few more How’s it going? texts before returning to his vacation. I was surprised by how little I thought about Seth, how I didn’t need him during such a stressful time. Shay called whenever she could, until I promised her I was really, really, truly fine and she should use her breaks to find some California friends. By the end of the week, the flood of origami cranes dwindled to two or three a day.

I was relieved.

Mom went back to work designing window treatments and Dad resumed his twelve-hour shifts, leaving me with my laptop and the online East End troll mill.

Nobody knew who had started the school slam pages or how they had blown up all over Long Island to the delight of the gadflies. But they were full of horrible comments about people’s appearances, and mental health, and family crises. The slam pages were pure evil. Everyone walked on eggshells, afraid one wrong move would make them slam-page targets.

The incident made me an instant target. And every comment, even the nice ones, caused my heart to race and my stomach to sink, but I couldn’t stop myself from reading.

If that were my daughter, I’d kick her ass a second time for pulling that stunt.

The world needs more heroic people.

She’s hot. I’d hit that.

Yeah, if you like Al Qaeda looking bitches.

“Very original,” I said to Shay, who was going through the slam page with me on her lunch break.

“At least they didn’t say your ass was fat.” Somebody once called Shay a fat-ass on the slam pages, which was ridiculous because Shay’s entire body was tiny. That one comment made Shay eternally ass-obsessed.

“I just remembered the guy called me an A?rab right before the incident,” I said.

“You get that a lot,” Shay said. “Somebody should write a ‘Geography for Dumb Racists’ book.”

“We could send it to him in prison. A Sadie care package.” I was half serious.

“Is he going to prison?”

Until that moment, I had assumed he was going to prison for a long, long time. A wave of anxiety swelled inside me. “I hope so.”

Lucky for me, the Hamptons Hero story was soon overshadowed by the Hamptons Hoodlum story about a local teen Meals on Wheels volunteer who had been caught stealing from elderly people to feed her shoe-shopping habit. I preferred to be me�ass crack, larva face, and all�than the shamed Hamptons Hoodlum.

Mom woke me up early for my appointment. I couldn’t wait to get rid of the itchy bandage. I had never been so excited to shower and hopefully smell like a human being again. I shuffled out to the back porch and stood there for a long time with my face up to the sky, grateful to be breathing better. I wandered through the neatly groomed rows of flowering vegetables, then climbed up the back porch steps and sat on the cushioned wicker chair in the shaded corner next to Mom, who was having her tea.

My swollen face changed color every day. One day it was purple, like the inner petals of a crocus flower, then it faded to hyacinth blue until it settled on the brownish-gold

hue of a smashed sunflower. Each time it changed, Mom took a picture.

“In case they need it for the trial.”

“I’m sure they don’t need to know how my bruise changes color.”

“They might, Sadie.” She dropped a pinch of rose petals into her teacup and set it on the saucer. “Are you able to do with just the ibuprofen today?”

“Yes, Mom. I’m not addicted to painkillers. Stop worrying.”

“I’m not worrying.”

“Mom?”

“Yes, hon?”

“I think I’m ready for pancakes.”

Farmer Brian had cleaned up the parking lot and hosed it down. As far as I could see, there were no remnants of blood or glass or honey. I eased back into work, handling the customers while Daniela did the stacking and rearranging. During break, I sat on a wooden crate under the willow tree and ate a quart of strawberries while the weekend traffic crawled by like a long, impatient caterpillar looking for a sea bath and some steamers with butter.

Sissy and old Mr. Upton wandered in during the afternoon lull.

“How are you feeling, Sadie?” Sissy asked while Mr. Upton examined snap peas like a jeweler studying diamonds.

“I’m okay. Thank you for the flowers, by the way.”

“I’m still shaken up. I can’t imagine how you’re doing it, being back here.” Sissy walked around to the side of the counter and put her hand on my shoulder. I felt a tickle inside, like there was a cry trying to surface. “Take care, dear,” she said.

Mr. Upton nodded and gave me a wink before he took Sissy’s arm and shuffled toward the old Lincoln.

City people came in to load up on corn and watermelon and cheese and honey to drizzle on the cheese. After the farm stand, they would stop at Citarella for baguettes and Tate’s cookies, and then they’d cozy up on their rental porches, taking in the sea air and dressing fancy for casual dinners.

The city people probably didn’t know me or what had happened in the parking lot.

But the locals knew.

“Sadie, wow. You look so good.” Hannah S. blindsided me while I was bent over a shipment of cherries.

“Thanks, Hannah. And thanks for all the cranes.” I wiped cherry juice on my apron. “You’re really good at origami.”

Hannah flashed me a smile. “So . . . I’m guessing you’ll be at Shawn’s white party?”

I had forgotten about Shawn’s white party, a variation of his usual Fourth of July tradition. By the look on Hannah’s face, she was going. And I assumed all the gadflies and ruffians would be there.

“Not sure. I’ll keep you posted.”

Did you know that there are over a thousand causes of vaginal itch? Shay texted randomly.

I laughed out loud as I waited on my willow crate for Dad to pick me up.

If it had been last summer, Shay and I would have met at her house before the party. Shay would have been wearing a white strapless pantsuit with funky white hair feathers and red lipstick. We would have shown up fashionably late, and Shawn’s new girlfriend would have given us jealous looks because we’d known Shawn since he was a bucktoothed kid with ADHD and a huge Pok.mon collection. We would have eaten marshmallows and vanilla milk shakes and whatever else people ate at white parties, and watched Seth and those guys do vodka shots off ice sculptures until they dove backward into the pool, messing up their crisp white linen shirts. And Shay and I would have left fashionably early to get pizza before the pizza place closed. We’d have sat on the curb in the middle of town in our dirty white clothes, eating and laughing and making fun of the people who took white parties too seriously.

But it wasn’t last summer. Shay was in California. And I’d been through an incident.

Shawn’s white party would be all lameness and emptiness.

It would be white noise.

When Dad and I pulled up in the ice cream truck, Mom was on the porch frantically waving a piece of paper.

“Maybe Grandma finally won the lotto,” I said.

“Sadie.” Mom bent to catch her breath. “You’ve been invited to be an honoree at the Rotary Club Homegrown Hero Award Luncheon.” She handed me a red-edged invitation. “This is fantastic.” I stared at the letter.

You have been nominated for this special honor . . . Please join us . . .Lunch . . . Homegrown Hero . . . Other young community leaders nominated from local junior classes . . .

“Mom, I can’t go to this. I’m not a community leader. I did one thing.”

Her smile disappeared. “Of course you’re going to this.”

“Dad, please don’t make me go. I helped a baby for, like, two minutes. This is for people who do real community service.”

Dad studied the letter. “I gotta go with your mother on this one, Sadie. They selected you. It’s an honor! We have to go.”

We went back and forth over our rice and kebabs and vanilla pudding, and in the end, honor won over Please don’t make me do this.

At least I had an excuse to miss the white party. Two events in one day would be more than my spleen could handle.

Older

Older